Pre-Incorporation IP: Who Owns What You Built Before?

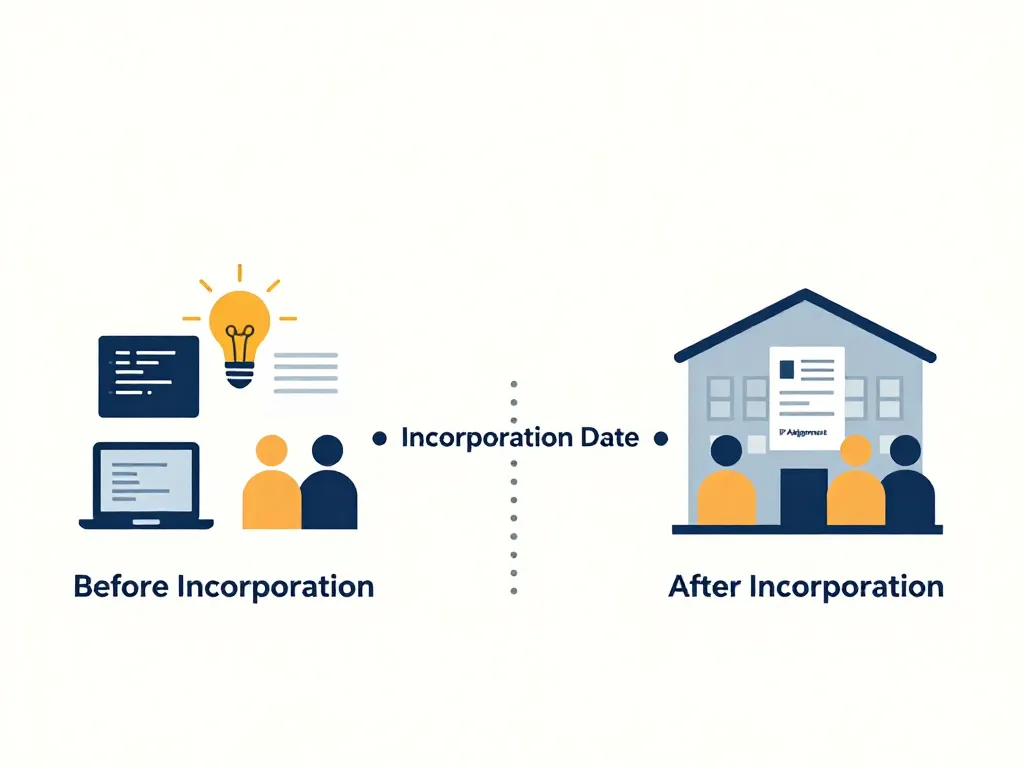

You and your cofounder spent eight months building a prototype. Late nights after your day jobs, weekends lost to debugging, a Figma file with 47 iterations of the UI. Then you incorporate. You file the paperwork, open a bank account, and assume everything you built together now belongs to the company.

Except it doesn't. Not automatically.

Pre-incorporation IP — the code, designs, algorithms, brand assets, and creative work produced before a company legally exists — belongs to the individuals who created it. Not to the startup. Not to "the team." To specific people. And when cofounders haven't explicitly addressed this, it becomes one of the most common and most destructive sources of conflict in early-stage companies.

This article walks through exactly how pre-incorporation IP ownership works, where cofounders typically get it wrong, and what you can do — today — to protect both the company and your relationships.

Key Takeaways

- Any code, designs, or other IP created before incorporation legally belongs to the individual who made it — not to the startup — unless a written assignment agreement transfers ownership to the company.

- Execute a formal IP assignment agreement at or immediately after incorporation that covers every piece of pre-incorporation work, and ensure every cofounder signs it.

- Create a detailed inventory of all pre-incorporation IP that documents who created each asset, when, with what resources, and whether any third parties contributed.

- Review every cofounder's prior employment agreements for invention assignment clauses that could give a former employer a claim over your startup's core technology.

- Handle IP assignment while cofounder relationships are strong — waiting until a dispute, fundraise, or departure makes the process exponentially more expensive and contentious.

Why Pre-Incorporation IP Doesn't Automatically Belong to the Company

Here's the legal default that surprises most founders: if you write code on your own laptop, on your own time, before a company exists, you own that code. Full stop.

A company can only own intellectual property in two ways:

- It was created by an employee within the scope of their employment (the "work for hire" doctrine)

- The creator explicitly assigned it to the company through a written agreement

Before incorporation, there's no employer. There are no employees. There's no entity that can receive an assignment. So everything created during that pre-incorporation phase lives in a legal gray zone — owned by whichever individual actually made it.

This matters enormously because investors, acquirers, and partners will eventually ask a pointed question: Does the company actually own its core technology? If the answer is unclear, deals fall apart.

The "We're Partners" Assumption

Many cofounders operate on a handshake understanding: "We're building this together, so we both own it equally." That feels right emotionally. Legally, it's almost never true.

Consider this scenario:

Nadia and James decide to build a SaaS product for restaurant inventory management. Nadia writes the entire backend over four months. James handles market research, talks to potential customers, and creates a pitch deck. They incorporate as 50/50 partners.

Six months later, James wants to pivot. Nadia doesn't. The relationship breaks down.

The question: Who owns the backend code that is the product?

The answer: Nadia does. She wrote it before incorporation, and there's no signed IP assignment transferring it to the company. James contributed research and a pitch deck — valuable work, but not the core technology. The company they incorporated may have no legal claim to its own product.

This isn't a hypothetical edge case. Variations of this scenario play out constantly in early-stage startups.

What Counts as Pre-Incorporation IP?

Cofounders tend to think of IP narrowly — as patents or proprietary algorithms. In reality, pre-incorporation IP includes anything with potential legal protection:

- Source code (the most common and most contested)

- UI/UX designs, wireframes, and prototypes

- Brand elements: logos, names, domain names

- Written content: pitch decks, business plans, marketing copy

- Databases and datasets you compiled

- Trade secrets: customer lists, pricing models, supplier contacts

- Inventions that could be patented

- Architectural decisions and technical documentation

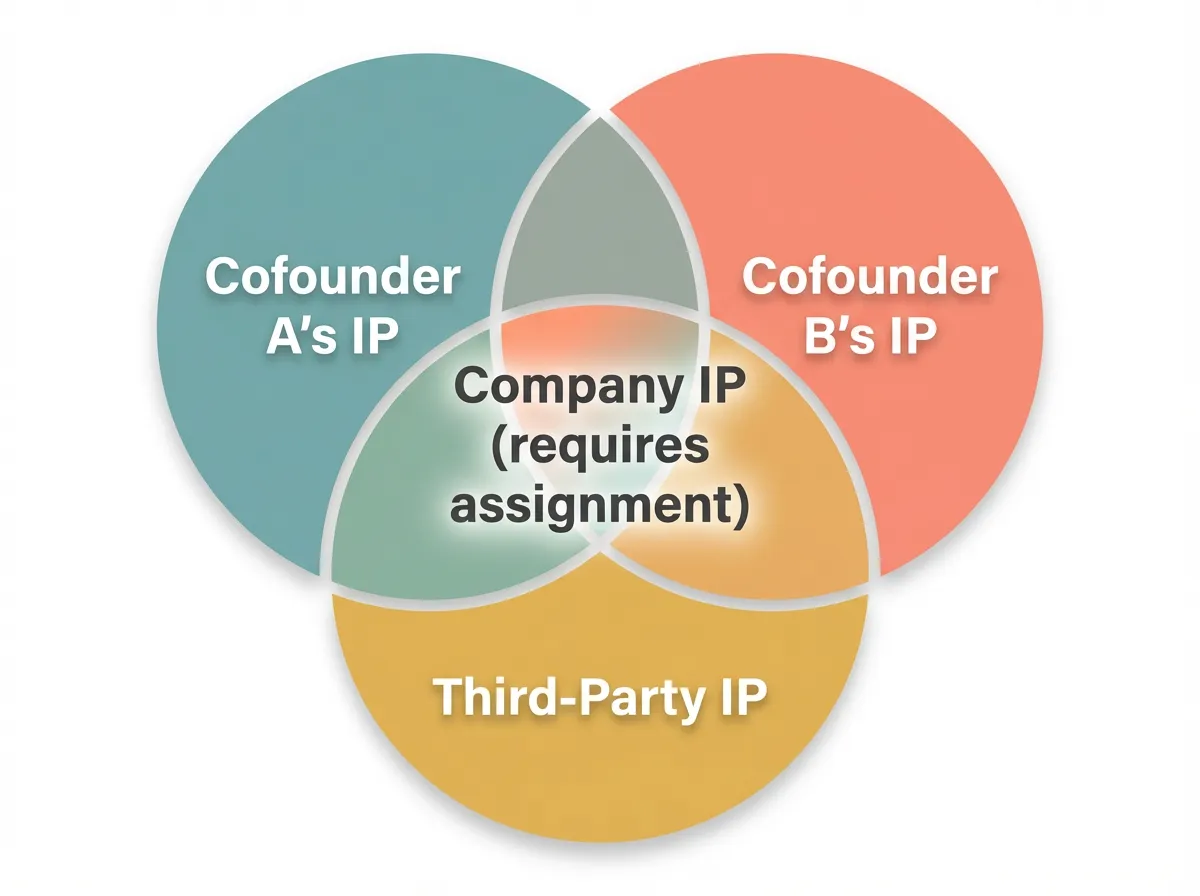

If a cofounder created it, they own it — unless a written agreement says otherwise.

The Three Scenarios That Create the Biggest Disputes

Scenario 1: One Cofounder Built Everything Technical

This is the Nadia-and-James situation above. One cofounder is the builder; the other is the business person. The builder contributed the product itself. The business cofounder contributed strategy, relationships, maybe even initial funding.

When things go well, nobody cares about the legal technicalities. When things go badly, the technical cofounder holds leverage that can effectively hold the company hostage — or, conversely, the business cofounder might argue the technical work was done for the partnership and should belong to the company.

Neither position is entirely fair, and neither is automatically true under law.

Scenario 2: A Cofounder Used Their Previous Employer's Resources

This one is more dangerous than most founders realize. If a cofounder built the prototype using their employer's laptop, their employer's software licenses, or on their employer's time, that employer may have a claim to the IP — regardless of what the cofounders agreed among themselves.

Most employment agreements contain an invention assignment clause that gives the employer ownership of anything created using company resources or related to the company's business. A cofounder who unknowingly violated their employment agreement can bring a ticking legal bomb into your startup.

Scenario 3: A Third Party Contributed Work

Maybe a friend helped design the logo. A freelancer built the landing page. A former colleague contributed a critical algorithm "as a favor." None of them signed anything.

Every one of those contributions is owned by the person who made them. Without a written assignment, your company doesn't own its own logo, its own website, or a piece of its own technology.

How to Fix Pre-Incorporation IP Ownership

The good news: this is fixable. The less-good news: it requires intentional action, and the longer you wait, the harder and more expensive it becomes.

Step 1: Inventory Everything That Was Created Before Incorporation

Sit down with your cofounders and make a comprehensive list. Be thorough. Include:

- Who created each piece of IP

- When it was created

- What tools and resources were used

- Whether any third parties contributed

- Whether anyone was employed elsewhere at the time

This inventory becomes the foundation for everything that follows.

Step 2: Execute an IP Assignment Agreement

This is the critical document. An IP assignment agreement (sometimes called a "Confirmatory IP Assignment" or "Technology Assignment Agreement") formally transfers ownership of pre-incorporation IP from the individual creators to the company.

Key elements it should include:

- Identification of the IP being transferred (reference your inventory)

- Confirmation of full assignment — not a license, but complete transfer of ownership

- Representations and warranties that the assignor has the right to assign (they didn't create it using an employer's resources, they haven't previously assigned it to someone else)

- Consideration — what the assignor receives in exchange (typically their equity in the company)

- Signatures from every cofounder

This agreement is typically executed at or shortly after incorporation. Many attorneys include it as part of the standard incorporation package. If yours didn't, address it now.

Step 3: Check for Third-Party Claims

Go back to your inventory. For any IP that might be entangled with a cofounder's previous employer or a third-party contributor:

- Review employment agreements for invention assignment clauses

- Get written assignments from any freelancers or friends who contributed

- Consult an attorney if there's any ambiguity about whether a previous employer could claim ownership

It's far better to discover these issues now than during a due diligence process when a $2 million seed round is on the line.

Step 4: Include IP Assignment in Your Cofounder Agreement

Your cofounder agreement should explicitly address IP ownership — both pre-incorporation and ongoing. The relevant clauses should cover:

- Assignment of all prior IP related to the company's business

- Ongoing assignment of any IP created by cofounders in connection with the company

- Disclosure obligations — cofounders must disclose any IP they develop that might be relevant

- Separation provisions — what happens to IP if a cofounder leaves (spoiler: it stays with the company)

Tools like Servanda can help cofounders structure these agreements clearly, ensuring both pre-incorporation IP and ongoing contributions are formally addressed before misunderstandings become disputes.

Step 5: File and Maintain Your Records

Signed agreements are worthless if you can't find them. Store your IP assignment agreements, cofounder agreements, and IP inventory in a secure, accessible location. Many founders use a shared legal folder in their cloud storage with restricted editing permissions.

What Happens If a Cofounder Refuses to Assign Their IP?

This is the nightmare scenario, and it does happen. A cofounder decides they want to leave and take "their" code with them. Or they want to renegotiate their equity in exchange for signing the assignment.

If there's no signed agreement, your options are limited and expensive:

- Negotiation: Offer something of value (additional equity, a cash payment, adjusted vesting terms) in exchange for the assignment

- Implied license argument: You may be able to argue that the cofounder granted an implied license to use the IP by contributing it to the joint venture — but implied licenses are weaker than assignments and won't satisfy investors

- Litigation: As a last resort, you could sue for an equitable assignment — but this is costly, slow, and toxic to the company

The lesson: handle IP assignment before anyone has a reason to refuse.

A Quick Checklist for Cofounders

Before your next board meeting, investor pitch, or cofounder dinner, make sure you can check every box:

- [ ] We have a written inventory of all IP created before incorporation

- [ ] Every cofounder has signed an IP assignment agreement transferring pre-incorporation IP to the company

- [ ] We've verified that no pre-incorporation IP is subject to a previous employer's invention assignment clause

- [ ] All third-party contributors (freelancers, friends, advisors) have signed written assignments

- [ ] Our cofounder agreement includes clear IP ownership and assignment provisions

- [ ] All signed documents are stored securely and accessible to authorized parties

If you can't check all six, you have work to do this week — not this quarter, this week.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Don't rely on verbal agreements. IP assignments must be in writing to be enforceable in most jurisdictions. A handshake means nothing when a lawyer gets involved.

Don't assume incorporation fixes everything. Forming a company doesn't magically transfer IP into it. The company is a new legal entity that owns nothing until assets are formally assigned to it.

Don't use a generic template without customizing it. Your IP situation is specific to your team, your contributions, and your history. A one-size-fits-all document may miss critical details.

Don't ignore the problem because things are going well. IP ownership disputes almost never surface during good times. They surface during fundraising, acquisitions, cofounder departures, and pivots — exactly when you can least afford them.

Conclusion

Pre-incorporation IP is one of those issues that feels like a technicality right up until it isn't. The work you and your cofounders did before the company existed — those late nights, those prototypes, those early designs — that work has real legal ownership attached to it. And if you haven't formally transferred that ownership to the company, you're building on a foundation that could shift under you at the worst possible moment.

The fix isn't complicated. It requires honest conversations, a clear inventory, and signed agreements. Most cofounders can address this in a single focused session with an attorney or even on their own with the right templates.

Do it now. The conversations are easy when everyone is still excited about the same future. They become exponentially harder when that future starts looking different for different people.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who owns code written before a company is incorporated?

The individual who wrote the code owns it. Since no company existed at the time of creation, there is no employer-employee relationship and no entity that can automatically claim ownership. The code only becomes company property when the creator signs a written IP assignment agreement transferring it to the incorporated entity.

Do I need an IP assignment agreement if we're 50/50 cofounders?

Yes, absolutely. An equal equity split does not transfer IP ownership to the company — those are two separate legal concepts. Each cofounder must sign a written IP assignment agreement that explicitly transfers their pre-incorporation work to the company, regardless of how equity is divided.

What happens if a cofounder leaves and won't assign their pre-incorporation IP?

Without a signed assignment agreement, you may have to negotiate by offering additional equity or cash, argue for a weaker implied license based on their voluntary contribution, or pursue costly litigation for an equitable assignment. This is why it's critical to execute IP assignments early, before any cofounder has leverage or motivation to refuse.

Can a previous employer claim ownership of my startup's IP?

Yes, if a cofounder built the prototype using their employer's equipment, software licenses, or time — or if the work relates to their employer's business — the employer's invention assignment clause may give them a legal claim. Cofounders should carefully review their existing employment agreements and consult an attorney before assuming their side-project work is free and clear.

What should be included in a cofounder IP assignment agreement?

A strong IP assignment agreement should identify every piece of IP being transferred, confirm a full assignment of ownership (not just a license), include representations that the assignor has the right to assign, specify the consideration received in exchange (typically equity), and be signed by every cofounder. It should also reference a detailed IP inventory created collaboratively by the founding team.