Dual Career Couples: Who Compromises First?

It's 9 PM on a Tuesday. You're sitting across the dinner table from your partner, both of you exhausted, and the conversation lands on the thing you've been avoiding: one of you got a promotion offer—in another city. Or maybe it's smaller than that. Maybe it's who leaves work early when the school calls, or whose deadline gets to count as the "real" emergency this week.

For dual career couples, the question of who compromises first isn't a one-time negotiation. It's a recurring tension that surfaces in dozens of micro-decisions every month. And when those decisions pile up without a clear framework, resentment builds quietly—until it doesn't feel quiet anymore.

This article isn't about telling you who should sacrifice. It's about giving you practical tools to make these decisions together, so that compromise doesn't always fall on the same person's shoulders.

Key Takeaways

- Replace unspoken assumptions about whose career takes priority with explicit, time-boxed agreements that include a specific review date so open-ended sacrifices don't breed resentment.

- Use a structured five-step conversation framework—name the decision, state ideal outcomes, identify costs honestly, check for asymmetry, and formalize an agreement—instead of arguing career conflicts in real time.

- Make career compromises visible by writing down the major sacrifices each partner has made, and set a "rebalancing" trigger so one person doesn't absorb three or more major concessions in a row without discussion.

- Schedule a quarterly 30-minute career check-in to surface small tensions before they compound into the "resentment reckoning" that often blindsides couples 5–10 years in.

- When you're stuck, start by sharing fears rather than demands—understanding what each partner is afraid of losing shifts the conversation from adversarial to collaborative.

Why "Who Compromises First" Is the Wrong Question

Most couples approach career conflict as a zero-sum problem: one person wins, one person loses. But framing it this way almost guarantees someone ends up bitter.

The real question isn't who goes first. It's how do we build a system where both careers are taken seriously over time?

Research from Jennifer Petriglieri, author of Couples That Work, shows that dual career couples who thrive tend to move through deliberate negotiations at key transition points—rather than defaulting to assumptions about whose career matters more. The couples who struggle? They often never have the conversation at all. They just drift into patterns based on:

- Who earns more (the higher salary becomes the "primary" career by default)

- Gender norms (even in progressive households, women disproportionately absorb career sacrifices)

- Who complains less (the more accommodating partner quietly absorbs compromise after compromise)

- Whose career seems more "stable" (the freelancer, entrepreneur, or creative professional is expected to flex)

None of these defaults are agreements. They're assumptions. And assumptions don't survive stress.

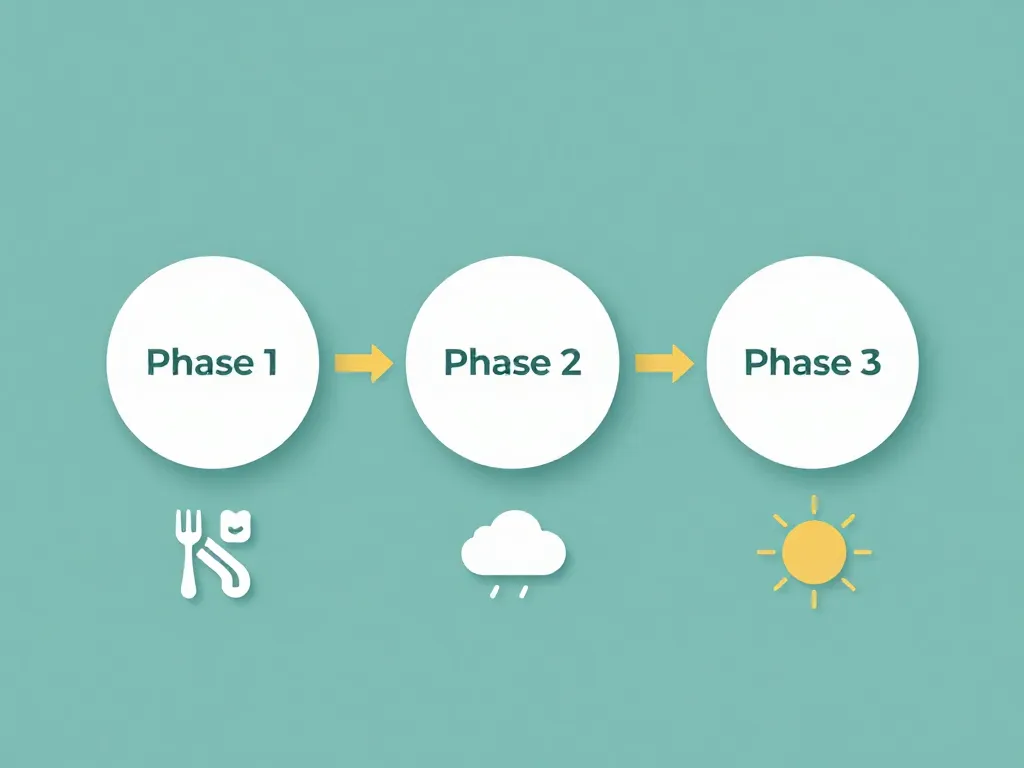

The Three Career Phases Every Dual Career Couple Faces

Petriglieri's research identifies three major transition points where dual career couples must actively renegotiate who compromises. Understanding where you are can help you stop arguing in circles.

Phase 1: The First Major Decision

This is the first time a real career conflict surfaces—a relocation, a demanding new role, the arrival of a child. Couples often stumble here because they've never had to prioritize one career over the other before.

What typically goes wrong: One partner makes a unilateral decision ("I already told them yes") or one partner silently defers without expressing what it costs them.

What to do instead: Treat it as a joint decision with explicit tradeoffs. More on this framework below.

Phase 2: The Resentment Reckoning

This usually hits 5–10 years in. One partner realizes they've been the one compromising repeatedly. Maybe they turned down opportunities, shortened parental leave, or put a degree on hold. The accumulated cost suddenly feels enormous.

What typically goes wrong: The compromising partner explodes or withdraws. The other partner feels blindsided: "You never said anything."

What to do instead: Build in regular check-ins (more on this below) so resentment doesn't have years to compound.

Phase 3: The Reinvention

Children leave, careers peak or plateau, and both partners re-evaluate what they actually want. This phase is an opportunity—but only if the couple can renegotiate without dragging old scorecards into the conversation.

What typically goes wrong: Past sacrifices become leverage. "I gave up X for you, so now you owe me."

What to do instead: Focus on what both of you want now, not on settling debts.

A Practical Framework: The Career Compromise Conversation

When a specific decision is on the table—a job offer, a schedule change, a relocation—use this structured conversation instead of arguing in real time.

Step 1: Name the Decision Clearly

Write it down. Not "we need to figure out our careers" but something specific:

"Priya has been offered a director role that requires 60-hour weeks for the first six months. How do we handle household and childcare responsibilities during that period?"

Vague problems produce vague arguments. Specific decisions produce actionable answers.

Step 2: Each Person States Their Ideal Outcome

Take turns. No interrupting. No rebutting. Each person describes what they'd want in a perfect world.

This matters because couples often skip to compromise before either person has actually articulated what they want. You can't find a middle ground if you don't know where the edges are.

Step 3: Name the Costs Honestly

For each possible path forward, both partners identify what it would cost them—professionally, emotionally, financially, personally.

This is where invisible labor becomes visible. "If I'm the one doing school pickup every day, I lose the ability to schedule afternoon client meetings, which is where 70% of my new business comes from." That's a cost that might not be obvious to your partner unless you say it plainly.

Step 4: Look for Asymmetry

Sometimes the decision isn't actually as balanced as it seems. Ask:

- Is this a reversible or irreversible decision? (Turning down a once-in-a-career opportunity is different from adjusting a schedule for one quarter.)

- Is the sacrifice equal in weight or is one person giving up significantly more?

- Is there a creative third option no one has mentioned? (Hiring help, negotiating remote work, delaying by six months.)

Step 5: Make an Explicit Agreement with a Time Limit

Don't just say "okay, we'll figure it out." Say:

"For the next six months, Priya will take the director role. Marcus will handle school pickups Monday through Thursday. We'll hire a babysitter for Fridays. We'll revisit this arrangement on September 1."

The time limit is critical. Open-ended sacrifices breed resentment. Time-boxed agreements feel manageable. Tools like Servanda can help you formalize these agreements in writing, so both partners have a clear reference point when it's time to revisit.

The Scorekeeping Trap (and How to Avoid It)

Let's address something uncomfortable: most couples keep score, even when they say they don't.

"I moved for your job in 2018." "I was the one who went part-time when the kids were small." "I've turned down three opportunities in the last two years."

Scorekeeping isn't inherently unhealthy. The problem is when it's unspoken, imprecise, and weaponized during fights.

Here's a better approach:

- Make the score visible. Literally write down the major career compromises each partner has made. Not as ammunition—as information. When both people can see the pattern, it's easier to correct imbalances before they become grievances.

- Distinguish between big and small sacrifices. Skipping a conference isn't the same as turning down a promotion. Not every compromise carries equal weight.

- Set a "rebalancing" trigger. Agree in advance: "If one of us has made three major career concessions in a row, we flag it and discuss before the next one."

What Real Couples Actually Do (Case Studies)

Example: The Turn-Taking Model

Sophia and Daniel, both in finance, agreed early in their marriage that they'd alternate who got "priority years." In even years, Sophia's career goals took precedence in household decisions. In odd years, Daniel's did. It sounds rigid, but they found it eliminated the draining negotiation over every individual decision. When Daniel got a Singapore posting in an "even year," they agreed to delay it by one year rather than abandon the system.

Why it worked: The framework was agreed upon before high-stakes decisions arose, so neither partner felt ambushed.

Example: The Primary Earner Trap

James earned roughly twice what his partner Alex did as a teacher. Over time, every career conflict defaulted to James's career taking priority—not because they'd agreed to it, but because "it just makes financial sense." By year eight, Alex had turned down a vice principal opportunity and a graduate program. When Alex finally named the resentment, James was genuinely shocked. They hadn't ever discussed the pattern.

What they changed: They stopped using current salary as the sole decision-making metric and started weighing career satisfaction, growth potential, and accumulated sacrifice alongside income.

Example: The Values Realignment

Mei and Chris hit Phase 3 when their youngest left for college. Mei had spent 15 years as the "flexible" career partner. She expected Chris would now defer to her goals. Chris, meanwhile, was at the peak of his career and felt it was the worst possible time to scale back. They spent months stuck because they were negotiating from different assumptions about what was "owed."

What broke the stalemate: They stopped talking about the past and focused on a single question: "What do we each want the next five years to look like?" Starting from a shared future—instead of a contested past—gave them room to build a new arrangement.

Five Principles for Ongoing Navigation

Beyond specific decisions, these principles help dual career couples maintain fairness over the long haul:

-

No permanent defaults. Any arrangement should have a review date. "For now" is fine. "Forever" is dangerous.

-

Career value isn't only measured in salary. Fulfillment, growth trajectory, flexibility, social impact, and intellectual engagement all count. If one partner's lower-paying career is treated as less important, you'll pay for it in resentment later.

-

The person compromising gets to define the cost. You don't get to tell your partner that their sacrifice "isn't a big deal." If it feels significant to them, it is.

-

Schedule the hard conversations. Don't wait for a crisis. A quarterly career check-in—even 30 minutes over coffee—can surface small tensions before they become big ones. Ask each other: "Is our current arrangement still working for you? What would you change?"

-

Protect the relationship from the competition. You are partners, not rivals. The moment career decisions start feeling like a power struggle, pause and reconnect with why you're building a life together in the first place.

When You're Stuck Right Now

If you're currently in the middle of a career conflict and can't find a path forward, try this tonight:

- Each partner writes down, separately: (a) what they want, (b) what they're afraid of losing, and (c) one creative option they haven't proposed yet.

- Exchange papers. Read silently.

- Then talk—starting with the fears, not the wants.

Fear is usually the real driver behind career conflicts. Fear of irrelevance, of being taken for granted, of watching your ambitions shrink. When you understand your partner's fear, the compromise conversation shifts from adversarial to collaborative.

Conclusion

The question "who compromises first?" will come up repeatedly in a dual career relationship. That's not a sign something is wrong—it's the nature of two ambitious people sharing a life. The couples who navigate it well don't eliminate the tension. They build frameworks for working through it that protect both partners' dignity and ambitions over time.

Start with one structured conversation using the framework above. Make the invisible visible. Set a review date. And remember: the goal isn't a perfectly balanced ledger. It's a relationship where both people feel seen, valued, and genuinely supported in becoming who they want to be.

That's not a compromise. That's a partnership.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do dual career couples decide whose career comes first?

Successful dual career couples avoid permanently prioritizing one career over the other. Instead, they use structured frameworks—such as alternating "priority years" or making explicit time-boxed agreements at each major decision point—so that both partners' ambitions are supported over time rather than one person silently deferring by default.

How do you stop resenting your partner for career sacrifices?

Resentment typically builds when compromises are unspoken, unacknowledged, and accumulated over years without review. You can prevent it by making sacrifices visible in writing, scheduling regular check-ins to assess whether the current arrangement still feels fair, and ensuring the partner who compromises gets to define the true cost of what they gave up.

Should the higher earner's career always take priority in a relationship?

Using salary as the sole decision-making metric is one of the most common traps dual career couples fall into. Career value also includes fulfillment, growth potential, flexibility, and personal meaning—so couples should weigh all of these factors alongside income when making joint career decisions.

How do you talk to your partner about a job offer in another city?

Treat a relocation offer as a joint decision by using a structured conversation: write down the specific decision, let each person state their ideal outcome without interruption, honestly name the professional and personal costs of each option, and look for creative third options like remote work or a delayed start date before making an explicit, time-limited agreement together.

What is the turn-taking model for dual career couples?

The turn-taking model is an approach where partners alternate whose career goals take priority during agreed-upon periods, such as alternating years. It works because the framework is established before high-stakes decisions arise, which removes the exhausting negotiation from each individual conflict and gives both partners confidence that their ambitions will be supported in turn.