Kids Playing Two Households Against Each Other: The Signs You Might Be Missing

Your daughter comes home from her dad's house and tells you she's allowed to stay up until 11 p.m. over there. Your son swears his mom said he doesn't have to do homework on weeknights anymore. Your youngest casually mentions that "Dad's girlfriend lets us eat candy for breakfast."

Something feels off, but you can't quite pin it down. You don't want to interrogate your child, and you definitely don't want to start another argument with your coparent. So you let it slide — once, twice, a dozen times — until one day you realize your kids have been running a quiet, sophisticated operation that would impress a seasoned diplomat.

Kids playing two households against each other is one of the most common — and most misunderstood — coparenting challenges. It doesn't mean your child is "bad." It almost never means your coparent is deliberately undermining you. But left unchecked, it creates confusion, erodes trust between households, and puts your child in a position no kid should occupy: the one holding all the power.

Here's how to spot it, understand it, and stop it.

Key Takeaways

- Close the information gap by establishing direct communication with your coparent — a shared rules document, weekly check-in texts, or a standing agreement to verify major requests before approving them.

- Never react immediately to what your child reports about the other household; instead, acknowledge it calmly and verify directly with your coparent.

- Stop using your child as a messenger for logistics, schedule changes, or any communication between households, as this gives them editorial power and keeps them in the middle.

- Align with your coparent on three to five non-negotiable areas like homework, bedtimes on school nights, and discipline, while accepting that minor differences between homes are normal.

- If your child knows that playing one house against the other leads to the parents communicating more — not less — the manipulation strategy loses its power.

Why Kids Play Two Households Against Each Other

Before we get into the signs, it helps to understand the why. Kids aren't born manipulators. They're adaptive. When a family splits into two homes, children lose a layer of structure they once took for granted. The rules that used to be enforced by two adults living under the same roof are now enforced — sometimes inconsistently — across two separate environments.

Kids notice gaps. And like water finding cracks in a foundation, they flow toward them.

It's developmental, not devious

Children test boundaries. That's a normal, healthy part of growing up. In a single household, a child might try playing Mom against Dad at the dinner table. In a two-household setup, the same impulse plays out with more distance — and less chance of getting caught.

Younger kids (ages 4–8) often do this without conscious intent. They repeat things inaccurately because their memory and comprehension are still developing. They genuinely might believe Dad said they could have ice cream for dinner when what Dad actually said was "maybe this weekend."

Older kids and teenagers? They're more strategic. They've learned that information asymmetry is leverage. If Mom doesn't know what Dad's rules are, there's room to negotiate — or fabricate.

It's also about emotional survival

Sometimes kids play households against each other not for candy or screen time, but because they're trying to manage something much bigger: loyalty, anxiety, or the fear that one parent will be hurt if they enjoy time with the other. A child who tells Mom that Dad's house is "boring" might be trying to make Mom feel better. A child who tells Dad that Mom is "too strict" might be testing whether Dad will rescue them from accountability.

The motivation matters because the response should be different.

The Signs Your Child Is Playing Both Sides

These behaviors exist on a spectrum from innocent to calculated. Most kids land somewhere in the middle.

1. Contradictory reports about rules

The classic sign. Your child claims that rules at the other household are dramatically different from yours — always in ways that benefit them.

- "Mom lets me play video games all day."

- "Dad said I don't have to practice piano anymore."

- "At Mom's house, I don't have a bedtime."

The tell: these reports almost always surface when your child is being asked to do something they don't want to do. The timing isn't coincidental.

2. Selective storytelling

Your child shares fragments of events from the other household — just enough to provoke a reaction, but not enough to give you the full picture.

For example, 10-year-old Maya tells her mom, "Dad's new girlfriend yelled at me." Mom is immediately alarmed and fires off a heated text. What actually happened: Dad's partner raised her voice to warn Maya that she was about to step into the street. The context was safety, not conflict. But Maya learned something powerful — a half-truth gets a big reaction.

3. Pitting parents against each other during decisions

This one is subtle. Your child asks you for permission to do something and frames it as already approved by the other parent.

- "Dad already said yes, so can I go?"

- "Mom said it's fine as long as you agree."

When you check with your coparent, they never said any such thing — or they said something much more conditional. Your child banked on the fact that you wouldn't verify.

4. Playing the sympathy card

Your child expresses distress about the other household in ways that feel designed to elicit a particular response from you.

- "I hate going to Dad's. There's nothing to do there."

- "Mom doesn't even care about me. She's always on her phone."

This is the hardest sign to evaluate because sometimes these statements are genuinely true and your child needs support. But if the complaints are vague, shift frequently, and escalate right before transitions, they may be a tactic — conscious or not — to avoid going to the other house or to get extra attention from you.

5. Gatekeeping information

Your child becomes the sole communication channel between households. They relay messages, interpret instructions, and report on what's happening at the other house. Over time, you realize you're relying on a 9-year-old for information that should come directly from your coparent.

This gives the child enormous power. They control what each parent knows. And they learn, fast, how to edit.

6. Escalating demands with a comparison hook

Every request comes with a comparison to the other household.

- "Dad bought me new sneakers, so I need new ones here too."

- "Mom lets me have my own Netflix account."

- "It's not fair that Dad's house has a pool and we don't."

This isn't just normal kid wanting-things. It's leveraging one household's resources to pressure the other, and it can quietly fuel resentment between coparents.

7. Behavioral shifts around transitions

Watch for patterns. If your child is consistently difficult in the hours before or after switching households — acting out, picking fights with siblings, suddenly "remembering" something upsetting about the other home — they may be processing the stress of the transition by trying to control the narrative.

What NOT to Do When You Spot These Signs

Before we talk about solutions, let's eliminate the approaches that make things worse.

Don't interrogate your child. "What exactly did your father say? Tell me his exact words." This puts your child in the witness stand and teaches them that information is currency — the opposite of what you want.

Don't bad-mouth your coparent. Even if you're frustrated, saying "Well, your mother obviously doesn't care about your education" hands your child more ammunition and deepens the divide.

Don't compete. If your child says the other house is more fun, resist the urge to one-up. The moment you start competing for your child's approval, you've handed them the scorecard.

Don't assume your coparent is the problem. The instinct is to blame the other household. But in most cases, the child is exploiting a communication gap — not a parenting failure.

What to Do Instead: Practical Steps

Close the information gap

The single most effective thing you can do is establish direct, consistent communication with your coparent about rules, expectations, and decisions. Your child's ability to play both sides depends entirely on you and your coparent not talking to each other.

This doesn't require friendly phone calls or lengthy coparenting meetings. It can be as simple as:

- A shared document listing household rules for both homes

- A weekly check-in text or email covering upcoming events, homework, and behavioral notes

- A standing agreement that neither parent approves major requests (sleepovers, purchases, schedule changes) without confirming with the other first

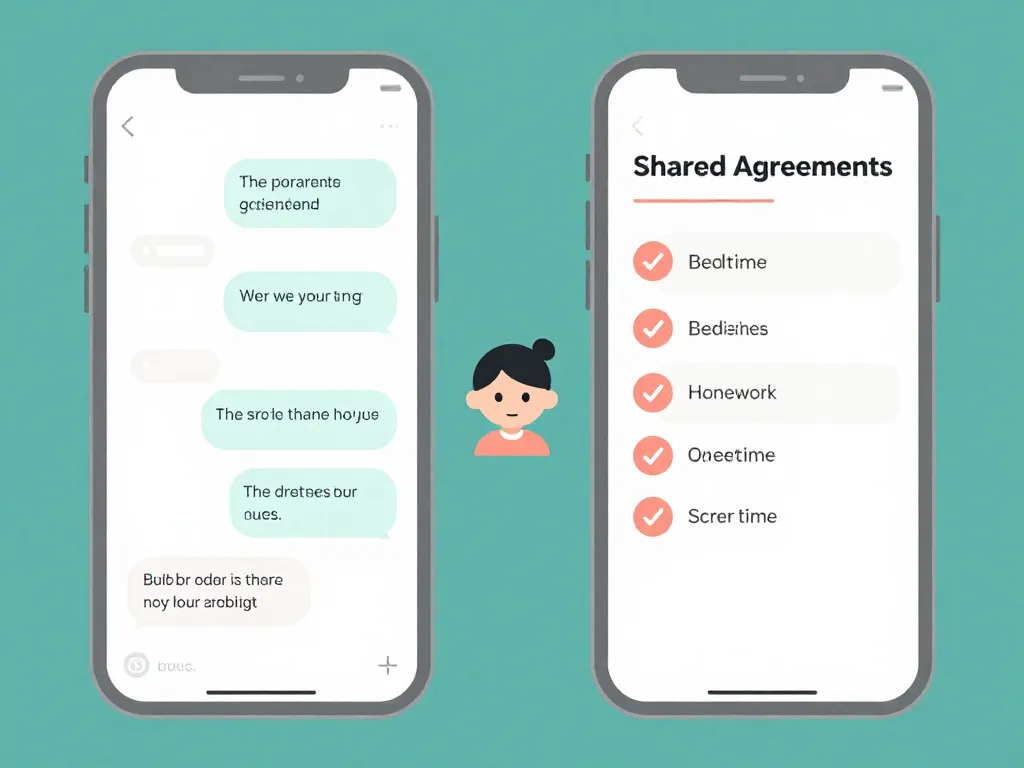

Tools like Servanda can help coparents create written agreements around rules and decisions, giving both households a shared reference point that a child can't easily work around.

Respond with curiosity, not reactivity

When your child reports something from the other household, resist the urge to react immediately. Instead:

- Acknowledge what they said. "That's interesting. Thanks for telling me."

- Avoid judgment. Don't praise or criticize what supposedly happened at the other home.

- Verify independently. If it matters, check with your coparent directly. Don't make your child the messenger.

- Set your own boundary. "In this house, our rule is lights out at 9. That's the rule here regardless of what happens elsewhere."

Name the behavior gently

With older kids, it's okay to name what you're seeing — without shaming them.

"I've noticed that when you don't want to do something here, you tell me it's different at Dad's. I'm not upset with you. But the rules here are the rules here, and I'm going to check with Dad directly when I need to."

This removes the payoff. If your child knows that playing one house against the other will result in the parents communicating more — not less — the strategy loses its power.

Build consistency where you can

You and your coparent don't need to have identical rules. Different households can have different structures, and kids are remarkably good at code-switching between environments. But on the big things — screen time limits, homework expectations, discipline approaches, bedtimes on school nights — alignment matters.

Pick three to five non-negotiable areas where you'll maintain consistency. Let the rest go. Your child having different snack rules at each house isn't a crisis. Your child believing homework is optional at one house is.

Don't make your child the messenger

This is worth repeating because it's so common. Every time you say "Tell your mother I need the soccer cleats back" or "Ask your dad if he can switch weekends," you're putting your child in the middle — and giving them editorial power over the message.

All logistical communication should flow directly between coparents. Period.

Watch for deeper issues

If your child's manipulation is persistent, escalating, or accompanied by anxiety, withdrawal, or depression, it may be more than normal boundary-testing. Consider involving a family therapist who specializes in children of divorce. A neutral third party can help your child process loyalty conflicts and develop healthier ways to communicate their needs.

When Coparents Disagree About Whether It's Happening

One of the most frustrating dynamics is when one parent sees the manipulation clearly and the other dismisses it. "She doesn't do that with me" or "You're reading too much into it."

This is common. The child may genuinely behave differently in each household, or one parent may be less attuned to the patterns. If you're in this situation:

- Lead with specific examples, not generalizations. "Last Tuesday, she told me you said she could skip soccer. Did you say that?" is more productive than "She's always lying about what you tell her."

- Propose a simple verification system. "Let's agree that for any schedule changes or permission requests, we text each other to confirm."

- Focus on the behavior, not blame. This isn't about who's a better parent. It's about closing a gap your child is exploiting.

The Long Game

Kids who learn that playing two households against each other works will carry that skill into adulthood — into relationships, workplaces, and friendships. The patterns you interrupt now aren't just about making coparenting smoother. They're about teaching your child that honesty and direct communication get them further than manipulation.

The goal isn't to punish your child for being resourceful. It's to build a coparenting structure so transparent and well-coordinated that manipulation simply doesn't work.

Conclusion

Kids playing two households against each other is almost never about a "bad kid" or a "bad coparent." It's about gaps — in communication, in consistency, in structure — that children naturally exploit. The signs range from contradictory rule reports and selective storytelling to emotional manipulation and gatekeeping information between homes.

The fix isn't surveillance or interrogation. It's closing the gap between households through direct communication, shared agreements on the things that matter most, and a calm, consistent refusal to let your child be the messenger. When both parents are on the same page — even if they're in different books — kids lose the incentive to play both sides and gain something far more valuable: the security of knowing that the adults in their life are working together.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my child lie about the rules at their other parent's house?

Most children aren't deliberately lying — younger kids often misremember or misinterpret what a parent said, while older kids may strategically exploit the fact that their parents don't compare notes. This behavior is driven by normal boundary-testing amplified by the communication gap between two separate households. The best response is to verify claims directly with your coparent rather than interrogating your child.

How do I stop my kid from manipulating me and my coparent?

The most effective strategy is to close the information gap between households by establishing direct, consistent communication with your coparent about rules, permissions, and expectations. When your child sees that both parents verify information with each other before reacting, the payoff for manipulation disappears. Tools like Servanda can help by creating shared written agreements that give both homes a clear reference point.

Is it normal for kids to act differently in each parent's house?

Yes, children are naturally skilled at adapting to different environments and can code-switch between two sets of household norms. Different rules for minor things like snacks or weekend routines are perfectly fine and don't need to be identical. However, if your child is consistently reporting dramatic contradictions to avoid responsibilities, that's a sign they may be exploiting differences rather than simply adjusting to them.

Should I confront my child about playing both parents against each other?

With older kids and teenagers, it's appropriate to gently name the pattern you're seeing without shaming them — for example, saying "I've noticed you bring up Dad's rules when you don't want to follow ours, and I'm going to start checking with him directly." Avoid interrogating or punishing your child, as this teaches them that information is currency. The goal is to remove the incentive by making the strategy ineffective, not to make your child feel like they're in trouble.

When should I involve a therapist if my child is playing two households against each other?

If the manipulative behavior is persistent, escalating, or accompanied by signs of anxiety, withdrawal, or depression, it may go beyond normal boundary-testing and warrant professional support. A family therapist who specializes in children of divorce can help your child process loyalty conflicts and develop healthier communication skills. This is especially important if your child seems to be managing deep emotions — like fear of hurting a parent — rather than simply angling for extra screen time.