One Wants Kids, One Doesn't: Now What?

You're lying in bed on a Sunday morning, and your partner says something about a friend's baby shower. You feel your stomach tighten. Not because you don't love your partner—you do, deeply—but because you already know where this conversation leads. One of you lights up at the thought of tiny shoes and bedtime stories. The other feels a quiet dread, or maybe just… nothing. No pull. No longing.

When one partner wants kids and the other doesn't, it can feel like you've hit an invisible wall in an otherwise loving relationship. This isn't a disagreement about where to eat dinner or how to split chores. It touches identity, legacy, freedom, and the fundamental shape of your future. And unlike most conflicts, there's no obvious middle ground.

But "no obvious middle ground" doesn't mean "no path forward." It means the path requires more honesty, more patience, and more structure than most couples are used to. Here's how to walk it.

Key Takeaways

- Stop trying to persuade your partner and instead use parallel sharing—take turns speaking about your feelings without rebuttal—to break out of the debate loop.

- Get explicit about timelines and whether each person's stance is genuinely resolved or still uncertain, because the difference fundamentally changes what's possible.

- Explore the deeper fears and motivations beneath each person's position by answering reflective questions separately, then sharing the answers without trying to fix or convince.

- If you're somewhere in the middle, build structure with scheduled check-ins, written-down needs, a mutual decision deadline, and documented agreements using a tool like Servanda.

- Accept that if the deep work still leads to an impasse, parting ways is not a failure of love—it's an honest recognition that your life paths diverge.

Why This Disagreement Feels So Different

Most relationship conflicts have a compromise zone. You want a dog, they want a cat—you get both, or neither, or you foster for a while. But when one partner wants kids and the other doesn't, the math seems brutally binary. You can't have half a child. You can't parent on alternating weekends with yourself.

This perceived all-or-nothing quality is what makes the disagreement so terrifying. It introduces a question most couples spend years avoiding: Is love enough?

But before you spiral into that existential crisis, it's worth understanding something important: most couples who face this disagreement are not actually at the final crossroads they think they're at. They're often at the beginning of a conversation they've been avoiding, half-having, or having badly.

The Difference Between a Position and a Feeling

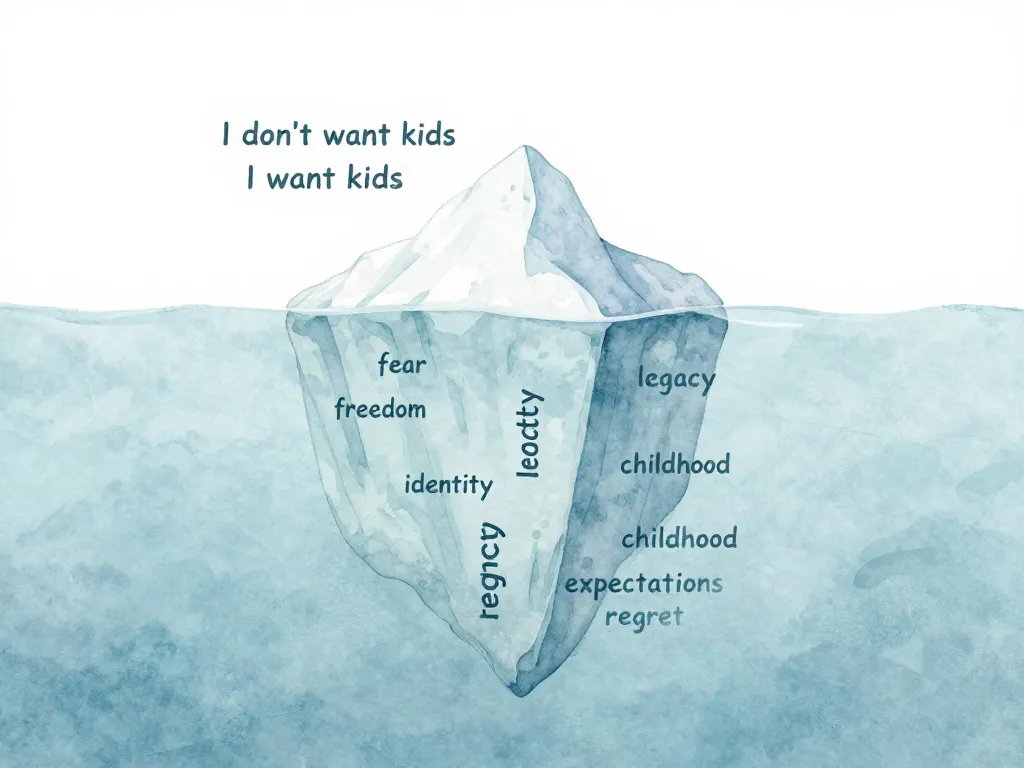

When someone says "I don't want kids," that's a position. But underneath it, there might be:

- Fear of repeating their own parents' mistakes

- Anxiety about financial stability

- A deep need for personal freedom and autonomy

- Concern about the state of the world

- A genuine, settled sense that parenthood isn't part of their identity

Similarly, "I want kids" might be driven by:

- A lifelong vision of family life

- Pressure from family or cultural expectations

- A biological urge that feels non-negotiable

- Fear of regret later in life

- A desire to give and receive a particular kind of love

The position is the tip of the iceberg. The conversation that actually matters is the one happening below the waterline.

Step One: Stop Trying to Convince Each Other

The single most common mistake couples make when one partner wants kids and the other doesn't is turning every conversation into a debate. One person presents their "case." The other rebuts. Both walk away feeling unheard, and the topic becomes radioactive.

Persuasion doesn't work here—not because your points aren't valid, but because this isn't a logical problem. It's an emotional and existential one. No one has ever been argued into genuinely wanting (or not wanting) a child.

Instead of debating, try parallel sharing:

- Set a timer for 10 minutes each

- One person speaks about their feelings—not their arguments—while the other listens without responding

- Switch roles

- After both have spoken, sit in silence for two minutes before discussing anything

This exercise sounds almost absurdly simple, but couples who've been locked in a persuasion loop for months are often stunned by what they hear when they actually stop preparing counterarguments.

Step Two: Get Honest About Your Timelines

One of the hidden tensions in this disagreement is often about when, not just whether. A partner who says "I don't want kids" at 27 may feel genuinely differently at 34. A partner who says "I want kids" may be responding to a ticking biological clock rather than a settled life vision.

This doesn't mean you should pin your hopes on someone changing their mind. That's a recipe for resentment. But it does mean you should get explicit about timelines:

- "I need to make this decision within the next two years because of my age."

- "I'm not ready now, and I honestly can't tell you if I'll ever be ready."

- "I've felt this way since I was a teenager, and nothing has shifted."

Each of these statements carries very different implications for the relationship. A partner who is uncertain is in a fundamentally different place than a partner who is resolved. And you deserve to know which one you're dealing with—even if the answer is uncomfortable.

Step Three: Investigate What's Underneath

This is where the real work begins. Once you've stopped debating and established honest timelines, you can start exploring the why behind each person's position.

Consider sitting down separately and writing answers to these questions:

For the partner who wants children:

- What does my life look like at 60 if I have kids? If I don't?

- Am I willing to raise children without this specific partner, or is it this person AND children that I want?

- How much of my desire comes from my own vision versus external expectations?

- What am I most afraid of if I don't have kids?

For the partner who doesn't want children:

- What does my life look like at 60 without kids? With them?

- Is my reluctance rooted in fear, or in a genuine sense of who I am?

- Are there specific conditions—financial, relational, logistical—that would shift my feelings?

- What am I most afraid of if I do have kids?

Share your answers with each other. Not to persuade. Not to fix. Just to be known.

A Real-World Example

Take Marco and Elena (names changed). Together for six years, deeply compatible in nearly every way. Elena had always imagined herself as a mother. Marco was firmly against having children—or so he said.

When they finally sat down to explore the why, Marco revealed something he'd never fully articulated: he was terrified of becoming his father, who had been emotionally absent throughout his childhood. His "I don't want kids" was actually "I'm afraid I'll fail at this in a way that damages someone permanently."

That didn't magically resolve things. But it transformed the conversation from a deadlock into something they could work with—together, and eventually with a therapist who specialized in family-of-origin issues. Marco didn't suddenly want children. But he stopped shutting the conversation down, and Elena stopped feeling like she was talking to a wall.

Step Four: Accept That This Might Be a Dealbreaker (And That's Not a Failure)

Here's the part nobody wants to hear: sometimes, after all the listening and exploring and therapy, you arrive at the same impasse. One person genuinely wants children. The other genuinely doesn't. And neither position is wrong.

This is not a failure of love. It's a collision of life paths.

Couples who stay together despite this fundamental misalignment often end up in one of two painful patterns:

- The Sacrifice Pattern: One partner gives in. They either have a child they didn't want or forgo one they did. Resentment builds slowly, like water behind a dam.

- The Delay Pattern: Both partners agree to "revisit it later," which often means one person is silently hoping the other will change while years pass.

Neither pattern leads anywhere good. If you've done the deep work and you're truly at an impasse, the most loving thing you can do may be to acknowledge it honestly—even if that means making an agonizing decision about the relationship's future.

Step Five: If You're Somewhere in the Middle, Build Structure

Many couples aren't at the extremes. One partner is a definite yes. The other is a hesitant maybe, or a "not yet," or a "possibly, but I need certain things first." If that's you, there's actually a lot to work with—but only if you build structure around the conversation.

Here's what that looks like in practice:

-

Set a specific check-in schedule. Agree to revisit the conversation every three or six months, rather than letting it surface unpredictably during arguments or emotional moments.

-

Define what each person needs to feel ready. Maybe it's financial benchmarks. Maybe it's progress in therapy. Maybe it's a certain level of stability in the relationship. Write these down.

-

Agree on a decision deadline. This isn't an ultimatum—it's a mutual acknowledgment that time is a factor and that indefinite ambiguity isn't fair to either person.

-

Formalize your agreements. When emotions run high and conversations span months or years, it's easy to remember things differently. AI-powered mediation platforms like Servanda can help couples document shared agreements and revisit them with clarity, ensuring that both partners stay accountable to what they've actually said—not what the other person remembers them saying.

-

Get outside support. A couples therapist who specializes in life-stage decisions can hold space for both of you in a way that's hard to do on your own. This isn't a sign of weakness. It's a recognition that some problems are too big for two people alone.

What Not to Do

A few pitfalls to avoid while navigating this:

- Don't issue ultimatums disguised as conversations. "If you don't want kids, I'm leaving" isn't a discussion. It's a threat. Even if that's where you end up, the process of getting there matters.

- Don't recruit allies. Bringing in friends, parents, or siblings to support "your side" will make your partner feel ambushed and harden their position.

- Don't make assumptions about the future. "You'll change your mind" is dismissive whether it's directed at the person who wants kids or the person who doesn't.

- Don't use hypothetical children as leverage in other arguments. The kid conversation needs its own space, separate from fights about dishes or in-laws.

- Don't catastrophize silence. If your partner needs a week to think after a heavy conversation, that's not abandonment. It's processing.

When to Seek Professional Help

Consider working with a therapist if:

- You've been having the same conversation for more than six months without progress

- One or both partners are avoiding the topic entirely

- The disagreement is leaking into other areas of the relationship

- Either partner is experiencing anxiety, depression, or grief related to the decision

- You're considering staying together while one partner secretly hopes the other will change

A good therapist won't tell you what to decide. They'll help you understand what you're actually deciding between—which is often more nuanced than "kids or no kids."

Conclusion

When one partner wants kids and the other doesn't, the path forward isn't about winning an argument or waiting someone out. It's about radical honesty—with your partner and with yourself. It's about separating positions from fears, timelines from assumptions, and love from compatibility.

Some couples will find more room than they expected. Others will face the painful recognition that their paths diverge. Both outcomes deserve respect.

What matters most is that you don't let this conversation happen passively—through silence, resentment, or hope that time will sort it out. You have agency here. Use it with care, use it with courage, and give your relationship the respect of a real answer, whatever that answer turns out to be.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a relationship survive if one person wants kids and the other doesn't?

It can, but only if both partners do the honest emotional work of exploring what's underneath their positions rather than debating surface-level stances. Some couples discover hidden fears or flexible timelines that create room for resolution, while others may need to lovingly acknowledge that their life paths are incompatible.

How do I talk to my partner about wanting kids without it turning into a fight?

Use a structured approach like parallel sharing: each person gets uninterrupted time to express their feelings—not arguments—while the other simply listens. Scheduling these conversations intentionally, rather than letting them erupt during emotional moments, also helps keep the discussion productive and safe.

Should I wait and hope my partner changes their mind about having kids?

Waiting passively for someone to change their mind typically leads to resentment and wasted time for both partners. Instead, set explicit timelines and check-in schedules so you're making an informed, mutual decision rather than drifting in ambiguity.

When should we see a couples therapist about the kids disagreement?

Consider seeking professional help if you've been going in circles for more than six months, if one of you is avoiding the topic entirely, or if the conflict is causing anxiety, depression, or spilling into other areas of your relationship. A therapist won't decide for you but will help you understand what you're truly deciding between.

Is it wrong to break up over disagreeing about kids?

Ending a relationship over a fundamental life-path difference is not a failure—it's one of the most honest and respectful choices you can make. Staying together while one partner sacrifices their deep desire often leads to long-term resentment, which can be far more damaging than a loving, clear-eyed separation.